Briefing: Westminster debate on the definition of “sex” in the Equality Act

This is our Parliamentary briefing for the debate on the definition of “sex” in the Equality Act, Westminster Hall, 12th June 2023. It’s also available to view/download as a PDF.

Background

- For Women Scotland is a women’s rights campaign group and we have been seeking clarification on the definitions of “sex” and “woman” in the Gender Representation on Public Boards (Scotland) Act 2018 (GRPBA) and Equality Act 2010 through the Scottish courts for a number of years. We won a judicial review at appeal in February 2022 where it was ruled that the redefinition of “woman” in the GRPBA – to include males with the protected characteristic of gender reassignment – was unlawful and outwith the competency of the Scottish Government who are limited to using Equality Act definitions of protected characteristics. The decision also stated that “sex” and “gender reassignment” are separate protected characteristics which should not be confused or conflated and that provision for women, by definition excludes biological males. [1]

- In a separate judicial review the first instance court ruled in December 2022 that the definition of “woman” given in the revised statutory guidance for the GRPBA – to include males with the protected characteristic of gender reassignment who hold a female Gender Recognition Certificate (GRC) – was lawful and consistent with the Equality Act. [2]

- We believe this ruling misinterprets the Equality Act and fails to properly apply the binding decision of the higher court in our first case. An appeal has been lodged with the Inner House and the substantive hearing is expected by late summer.

Our position

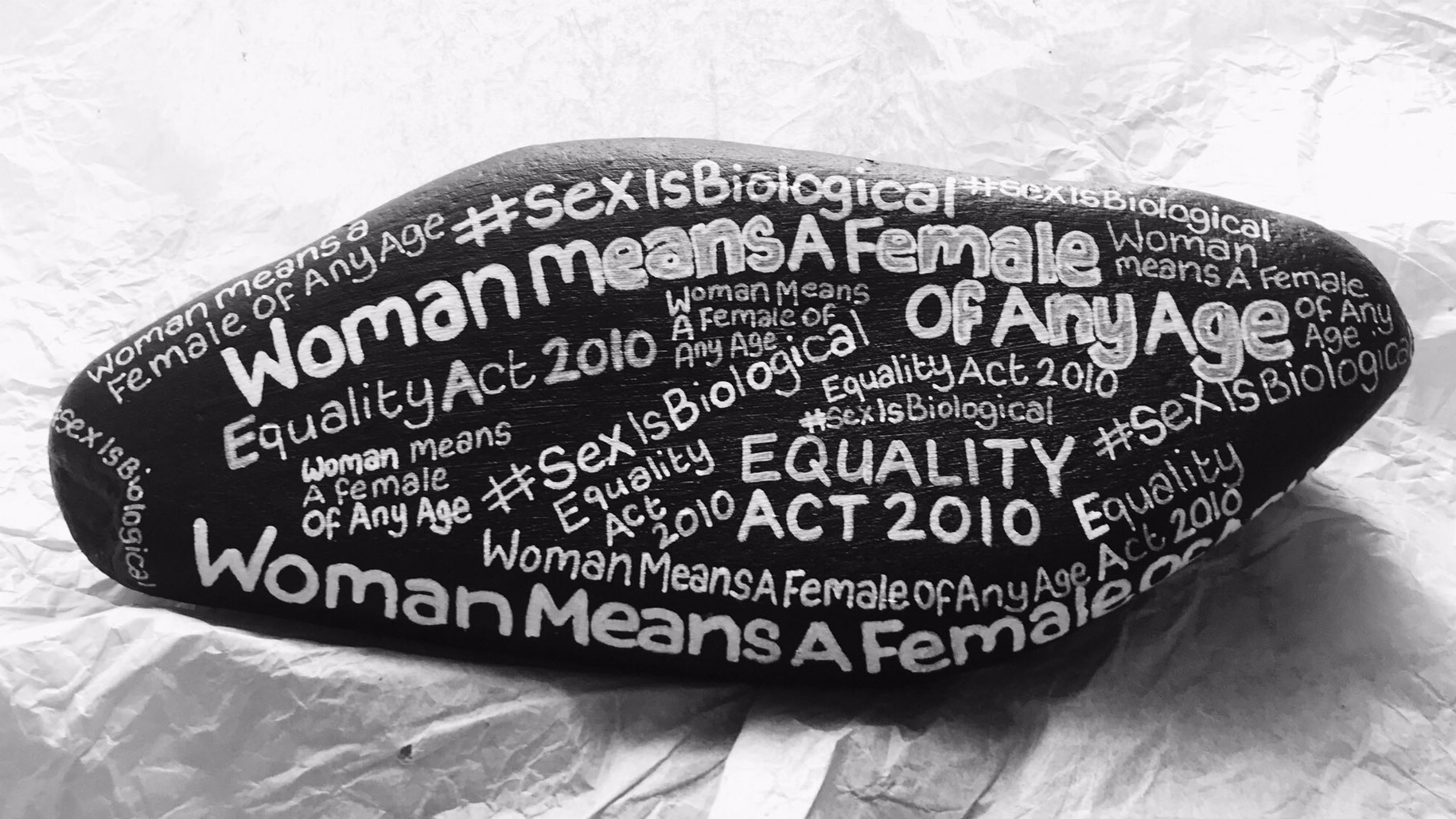

- Section 11 of the Equality Act defines the protected characteristic of “sex” in binary terms – it is a reference to being a man or a woman. Section 212 states that “woman” means “a female of any age”. We consider this to be quite clear and unambiguous, and the word “biological” is not necessary to provide clarity. Terms such as “biological sex” or “biological woman” contain a hopeless redundancy, because there is no such thing as “nonbiological sex” or a “nonbiological” woman”. For the purposes of the Equality Act there are simply “women” and “men” and the biological factual reality of two different sexes.

- The protected characteristics of “gender reassignment”, “pregnancy and maternity” and “sexual orientation” are all predicated on biological referents to “sex”:

(a) The concept of being able to claim protection against discrimination because of the protected characteristic of “gender reassignment” is dependent on a prior finding of what that claimant’s “sex” is. This results from the very definition in Section 7 of the Equality Act, which refers to such individuals being able to claim “gender reassignment” because of a process of changing physiological or other attributes of their sex.

(b) All of the references to “pregnancy and maternity” throughout the Equality Act are made in relation to, and only to, women. “Woman” necessarily involves a reference to female biology when used in relation to the Equality Act protections against discrimination because of pregnancy and/or maternity. It cannot have been the intention of Parliament to deny some women (who have obtained a male GRC) these protections.

(c) Similarly, the definition of “sexual orientation” in Section 12 of the Equality Act towards persons of the same sex, the opposite sex, or either sex must rely on “sex” being biologically defined and determined. The idea that a certificate can change an individual’s sexual orientation or transform a heterosexual relationship into a homosexual one (or vice versa) is absurd, and has the potential to undermine the Equality Act protections against sexual orientation discrimination by effectively depriving the very concept of any meaning.

- There is no other definition of “sex” or “woman” given within the Equality Act so it must be presumed that Parliament intended these terms of biology to be applied uniformly whenever used in the Equality Act. “Sex” cannot refer to biology for a woman’s protection against pregnancy discrimination but then switch to mean “certified sex” to exclude the same person from, for example, an all-women shortlist in provisions elsewhere in the same Act.

- There is no hierarchy among Acts of Parliament, other than the time when they were passed. And because Parliament cannot bind its successors this means that an earlier statute may be effected by a later statute. It is also the case that the provisions of an earlier statute may, by the requirements of a later statute, be repealed or suspended or disapplied by implication in any particular factual situation. [3]

- This means that Section 9 of the Gender Recognition Act 2004 (GRA) can only lawfully be read and be given effect subject to its consistency with the Equality Act 2010 (rather than the other way around). In the event of any conflict between their provisions the Equality Act prevails.

- Within the context of a proper interpretation of the Equality Act whereby “sex” refers to biological reality, the provisions of Section 9(3) GRA disapply and render wholly inapplicable the claims and legal fictions set out in Section 9(1) GRA 2004.

9(1): “Where a full gender recognition certificate is issued to a person, the person’s gender becomes for all purposes the acquired gender (so that, if the acquired gender is the male gender, the person’s sex becomes that of a man and, if it is the female gender, the person’s sex becomes that of a woman).”

9(3): “Subsection (1) is subject to provision made by this Act or any other enactment or any subordinate legislation.”

The issue

- There is always a risk in any appeal case that the previous erroneous court decision will not be overturned. This would be disastrous for women’s rights as “woman” as a biological class would no longer be a protected characteristic. Any legitimate aim in providing a single-sex service would, by definition be by “certified sex” and must include males with a female GRC. The exceptions in the Equality Act relating to gender reassignment become contested and unworkable, particularly as the lower court decision stated GRC holders may not even have this protected characteristic.

- The situation would be resolved in Scotland if the Inner House overturns the decision and recognises and affirms its previous judgment that sex is a biological category – and if the case is not further appealed. However, it would only be a “persuasive” ruling in the rest of the UK.

Suggested solution

- Any Statutory Instrument needs to put it beyond doubt that Parliament intended the Equality Act to protect people on the biological factual reality of two different sexes and that these protections are not lost on acquiring a GRC. This is also consistent with pre-existing common law [4] and, indeed, case law [5] post-dating the enactment of the GRA and Equality Act. We think it simplest if it is made clear that the claims of Section 9(1) GRA have been disapplied by virtue of Section 9(3) with the following addition to Section 11 Equality Act:

Section 11

In relation to the protected characteristic of sex–

(c) Section 9(1) Gender Recognition Act 2004 does not apply.

References

- For Women Scotland v Scottish Ministers [2022] CSIH 2

- For Women Scotland v Scottish Ministers [2022] CSOH 90

- Hamnett v Essex County Council [2017] EWCA Civ 6 [2017] 1 WLR 1155 per Gross LJ at § 26

See also For Women Scotland v Scottish Ministers [2022] CSOH 90 at § 53 where the Forensic Medical Services (Victims of Sexual Offences) (Scotland) Act 2021 disapplies by implication Section 9(1) GRA 2004 for the sex of a medical examiner to be requested with reference to the person’s biology and not “certified sex”. - Corbett v Corbett [1971] P 83, R v Tan [1983] QB 1053 and Bellinger v Bellinger [2003] 2 AC 467

- R (McConnell) v Registrar General for England and Wales [2020] EWCA Civ 559 [2021] Fam. 77 which concerned a woman, but who had the EA 2010 additional protected characteristic of gender reassignment and who had duly obtained under the GRA 2004 a full GRC to be treated as a man, albeit without losing a woman’s reproductive biological capacity to become pregnant – who carried and gave birth to a child. Notwithstanding the terms of Section 9(1) GRA 2004, the Court of Appeal held that McConnell still required to be registered under the Births and Deaths Registration Act 1953 as the “mother” of the child. The UK Supreme Court subsequently refused an application for permission to appeal to it against this decision.