Sex and the Hate Crime Bill

Taken from our Twitter thread.

We continue to be bemused by the determination of some in the Scottish Government and funded organisation to dismiss and undermine important work on sex in hate crime because it does not suit a predetermined political agenda.

In writing his report, Lord Bracadale consulted widely and concluded that an aggravator of gender (sex) should be added to the Hate Crime Bill.

While taking on board the objections raised by a tight knit group of Scottish organisations, he nevertheless felt that a stand alone offence would be superfluous and risk confusion. He was also concerned that momentum might be lost if there was further delay in meaningful action.

It is astonishing, therefore, that the same arguments which Lord Bracadale rejected were accepted without demur by the Cabinet Secretary when the Bill was drafted.

Perhaps more concerning has been the wholesale dismissal – indeed belittling – of some important bodies of work and trials on sex/misogyny. This either demonstrates an incomprehension of the purpose or findings of trials, or are a deliberate attempt to misrepresent.

As Bracadale reported, these trials did not change the law, yet nevertheless carried useful lessons for the police and public. Indeed, the very act of putting the policy together had a positive impact.

Therefore, dismissing the important Nottingham trial (which had an 87% approval rating) and the substantial report from Nottingham & Nottingham Trent Universities with a picture of a post-it note, as one member of the working group did last week, appears unprofessional at best.

It is interesting to note that this objection was based on the low number of charges which were brought under the Nottingham trial.

However, it is clear that the aim of women’s centres and police forces in England is far deeper and more holistic, involving changing awareness and disrupting behaviour: a preventative as much as a punitive approach. For example, see Women’s Centre Cornwall.

The sad fact is that there are many crimes on the statute book which disproportionately (or almost wholly) affect women. A tiny fraction of rape is reported, a fraction of that reaches court. Why add more crimes which might go unpunished or undetected?

Changing society and collecting data to enable resources to be deployed correctly would seem better than finding more people to criminalise. This focus on attitudes (police and public) has been the reason that many trials in England have been hailed as positive.

The report on the Nottingham trial identifies areas of success and areas for improvement. Ironically, of course, one of the objections in the focus groups was to the word “misogyny” itself which was felt to be elitist or academic and poorly understood.

Despite this clear and unequivocal finding, the Scottish Government appointed working group is to consider a stand alone offence of misogynistic harassment.

Sex and sexism are terms that are more widely understood – especially by women who have suffered from the latter. If we really wish to make laws with women’s experience in mind, why would the Scottish Government and women’s organisations ignore this?

While England has been gathering a substantial and impressive body of work on the subject thanks to police trials and work by the Fawcett Socitey and Women’s Aid, Scotland seems to have resolutely decided to ignore this evidence.

According to Sam Smethers, former CEO of the Fawcett Society: “We have to recognise how serious misogyny is. It is at the root of violence against women and girls. Yet it is so common that we don’t see it. Instead it is dismissed and trivialised. By naming it as a hate crime we will take that vital first step…But at a time of rising hatred in our society, much of it targeted at women, we have to take this seriously and act.”

The Scottish Government would no doubt claim that they are taking this seriously, but action is far off and far from guaranteed. Meanwhile, for reasons of politics or expediency, they appear to wish to reinvent the theoretical wheel in their approach and ignore the practical trials.

More and more police forces in England are beginning pilot schemes – and thus vital training and awareness. Meanwhile, Scotland is kicking the problem into the long grass with another working group tasked with finding a gap in law which eluded Bracadale.

We wonder if the Justice Secretary, Humza Yousaf, read any of these important studies? Did he speak to those who undertook the research? Has he asked the Fawcett Socitey, Women’s Aid and the Jo Cox Foundation why they believe this should be tackled by hate crime legislation and does he understand why?

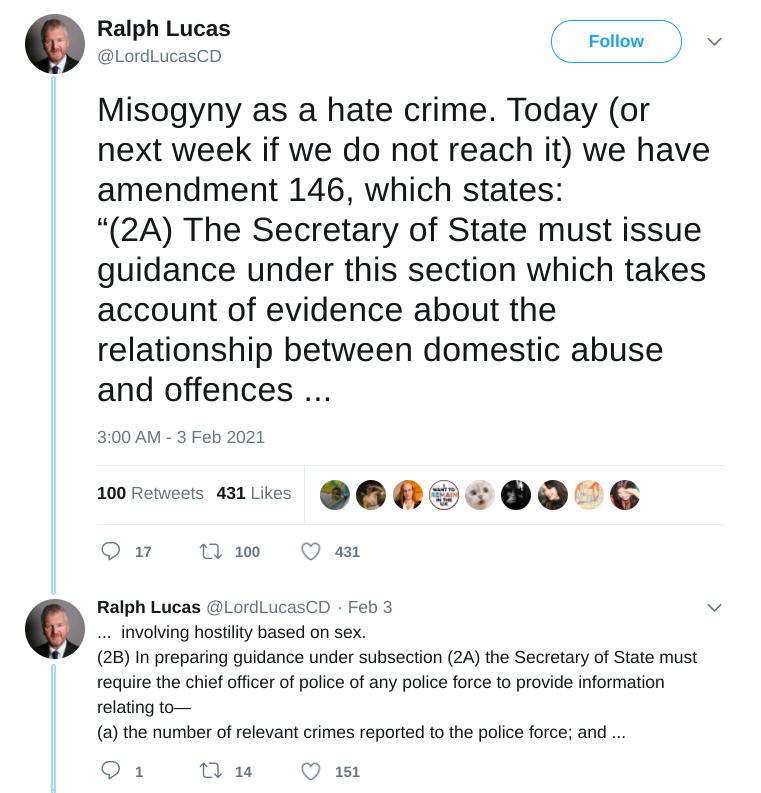

If not, this is surely an extraordinary dereliction of duty and the worst sort of Scottish Exceptionalism. The argument is “We can do better”, but without evidence or models for legislation, this is a leap of faith. Meanwhile, England is moving ahead, as indicated by tweets from Lord Lucas.

Unlike the women’s organisations in England pressing for change, the Scottish Government funded groups resistant to protecting women under this bill have not undertaken any work to explore the practical implications of this, or indeed any, approach.

They have not even consulted with the women who are, nominally, members. The CEO of Engender said herself at the recent AGM “I would like to be clear here – that Engender is not funded for a huge amount of engagement and are not presenting our work as advocating on behalf of the members or as representative of women.”

It seems that many objecting to adding sex, disagree with an aggravated model. This applies, however, to ALL characteristics and would, by logic, be a reason for Humza Yousaf to abandon the entire Bill.

All that has been held out to date as an example of good practice is the Domestic Abuse Act, referred to as “gold standard”. This act is, indeed, very important. It has also been drafted using gender neutral language, the other objection raised to adding sex to the Bill.

Is the approach by Scottish Government really to involve asking the same question, stacking the deck, and ignoring vital evidence until, eventually, they get the answer which they and other individuals desire?

As Bracadale and the English organisations note, legislation can send a message and it can affect awareness. The lack of legislation can also send a message. In this case, the Scottish Government signals that sexism is more complicated and of less pressing importance than other forms of hate.

While the working group deliberate toward an uncertain outcome, a sledgehammer is being taken to women’s freedoms and protections. There are no awareness programmes, no data is being collected. Long before legislation manifests, women will have borne the brunt of this inaction.