School guidance – third time lucky?

The first edition of Supporting Transgender Young People: Guidance for Schools in Scotland was published in 2017 by LGBT Youth Scotland. Two years later, the Scottish Government announced that it would be replaced. Ministers found the guidance risked excluding girls and was not legal, and they noted the diminished confidence in the guidance as a result, and that teachers would not use it.

New guidance was published by the Scottish Government in 2021 under an almost identical title (Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools: Guidance for Scottish Schools) and it is still in place today. In the foreword, Shirley-Anne Somerville, then Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills, states that the guidance “reflects the Equality Act 2010 duties on education providers with advice…on the practical application of those duties in a school setting”.

With the UK Supreme Court ruling in For Women Scotland v the Scottish Ministers, we know that the guidance most definitely does not reflect the Equality Act 2010 duties on education providers, and as such is unlawful, as recognised by Edinburgh City Council. But there have been other developments since 2021, primarily the Cass Review, Forstater v CGD Europe EAT, and also the recent case against Scottish Borders Council.

It is already clear that the existing guidance will once again need to be withdrawn. Currently the Scottish Ministers have only a few days left to do so willingly before they are taken back to court. The initial concern the Ministers expressed regarding diminished confidence in the guidance can only have increased as a result of both the first and now second editions being found unlawful. The third iteration must, at the bare minimum, get the law right. It should also align with other developments in the field, such as the Cass Review. But will it?

This blog examines some of the most contentious aspects of Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools (hereafter called ‘the guidance’) and discusses how likely it is that they will be revised in the third edition. This is a non-exhaustive list as there are many problems with the guidance, but it aims to address the most glaring issues.

1. Ideological Terminology and Framing

With the title, the 2021 guidance immediately labels all children that this guidance might relate to as ‘transgender’ and this terminology is applied throughout, with reference to ‘transgender pupils’ and ‘transgender young people’.

Automatically labelling any child caught up in this phenomenon as ‘transgender’ is an ideological position that is not rooted in objectivity or evidence. It is reflective of the fact that this guidance and its predecessor were drawn up directly by (1st edition) or in close consultation with (current edition) LGBT Youth Scotland, rather than independently and impartially.

The Cass Review does not generally refer to children as ‘transgender’ in either the interim report or final review. Instead it favours the term ‘gender-questioning’. The reasoning for this is clear within the two documents:

“[T]here is a lack of agreement, and in many instances a lack of open discussion, about the extent to which gender incongruence in childhood and adolescence can be an inherent and immutable phenomenon for which transition is the best option for the individual, or a more fluid and temporal response to a range of developmental, social, and psychological factors.”

(page 16, Cass Review Interim Report)

“[There is] lack of an agreed consensus on the different possible implications of gender-related distress – whether it may be an indication that the child or young person is likely to grow up to be a transgender adult and would benefit from physical intervention, or whether it may be a manifestation of other causes of distress.“

(p47 Cass Review Interim Report)

“Among referrals there is a greater complexity of presentation with high levels of neurodiversity and/or co-occurring mental health issues and a higher prevalence than in the general population of adverse childhood experiences and looked after children…A failure to consider or debate the underlying reasons for the change in the patient population has led to people taking different positions about how to respond to the children and young people at the centre of the debate, without reasoned discussion about what has led to their gender experience and distress”

(page 26, Cass Review)

“Peer influence during this stage of life is very powerful. As well as the influence of social media, the Review has heard accounts of female students forming intense friendships with other gender-questioning or transgender students at school, and then identifying as trans themselves”

(page 122, Cass Review)

“As set out in the section on brain development, maturation continues into a person’s mid-20s, and through this period gender and sexual identity may continue to evolve, along with sexual experience. Priorities and experiences through this period are likely to change…the Review heard accounts from young adults and parents about young people who felt certain about a binary gender identity in teenage years and then became more fluid in young adulthood or reverted to their birth-registered gender.”

(page 193, Cass Review)

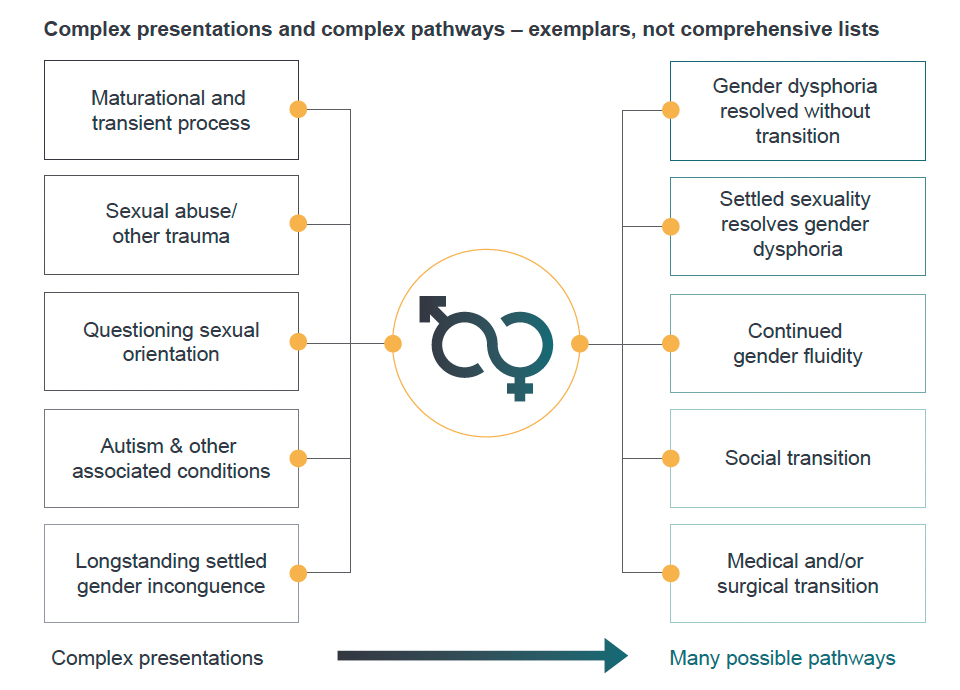

On page 57 of the Cass Review Interim Report, there is a diagram of exemplar presentations and pathways which is also illustrative:

The Cass Review highlights a fundamental lack of consensus about what gender incongruence in childhood actually signifies, therefore to label a child as ‘transgender’ is to come to a definitive conclusion that the evidence does not support.

Relatedly, the guidance states that “[t]he distinction between ‘gender non-conforming behaviour’ and transgender young people is that transgender young people are likely to be ‘persistent and insistent’ that their gender identity does not align with the sex they were assigned at birth“.

(page 14-15, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

This is effectively suggesting that teachers implement diagnostic criteria, when clinicians, who are actually qualified to do so, “are unable to determine with any certainty which children and young people will go on to have an enduring trans identity“.

(page 22, Cass Review)

Despite a clear ideological bias, the terminology and framing are unlikely to change. The Scottish Government’s reluctance to withdraw the current schools guidance, even though it is in clear breach of the law, suggests a dysfunctional attachment to its ideological position beyond reason.

Chance of change in the third edition: VERY LOW

2. Single Sex Provision

The guidance mandates a self-ID approach to the use of single sex provision. Some examples include:

“There is no law in Scotland which states that only people assigned male at birth can use men’s toilets and changing rooms, or that only people assigned female can use women’s toilets and changing rooms.”

(page 26, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

“It is…important that young people, where possible, are able to use the facilities they feel most comfortable with.”

(page 27, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

“For certain residential accommodation it is possible under exceptions provided by the Equality Act to treat a transgender young person differently in the provision of single-sex communal accommodation if this is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. This means that schools are not required to place a transgender young person in a dormitory that aligns with their gender identity if this treatment of them is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. This will require careful consideration.”

(page 32, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

“If a transgender young person wants to share a room with other young people who share their gender identity, they should be able to do so, as long as the rights of all those involved are considered and respected.”

(page 32, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

“if PE classes are organised by sex, a transgender young person should be allowed to take part within the group which matches their gender identity.”

(page 30, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

The UK Supreme Court clarified that in the Equality Act 2010, ‘sex’ means biological sex. The EHRC have advised the following:

“The law in Scotland requires schools, irrespective of pupils’ age, to provide separate toilet facilities for boys and for girls. Toilet cubicles are required to be partitioned and have lockable doors. Pupils who identify as trans girls (biological boys) should not be permitted to use the girls’ toilet or changing facilities, and pupils who identify as trans boys (biological girls) should not be permitted to use the boys’ toilet or changing facilities. Suitable alternative provisions may be required.”

This is very clear and as such it is untenable that the above sections can remain in the third edition of the guidance. Additionally, in April, after parents brought a case against Scottish Borders Council in relation to their child’s school only offering unisex toilets, the judge ruled that Scottish schools must adhere to The School Premises (General Requirements and Standards) (Scotland) Regulations 1967 and provide single-sex toilets for pupils. The following section will therefore need to be reworded as all toilets cannot legally be designated as gender neutral (unisex).

“there are a number of considerations to make in relation to the provision of toilets and changing rooms within schools…in summary this does not mean that all toilets need to become gender neutral.”

(page 26, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

Though the Scottish Government may have to be forced into it by the courts, there is no ambiguity here – these sections must change.

Chance of change in the third edition: VERY HIGH

3. Social Transitioning

The guidance advocates for social transitioning at school:

“Some tips for responding to a young person who talks to you about being transgender or about their gender identity include: Ask what name and pronoun you should use to address them. Check if that’s all the time or in certain circumstances” (page 21, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

“Teachers should respect a young person’s wishes and use the name/pronoun they have asked to be used.” (page 22, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

“If a young person in the school says that they now want to live as a boy although their sex assigned at birth was female, or they now want to live as a girl, although their sex assigned at birth was male, it is important to provide support and listen to what they are saying. If others deny this, it may have a detrimental impact on the young person’s wellbeing, relationships and behaviour and this is often clearly apparent to teachers, parents and carers.”

(page 13-14, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

The Cass Review specifically mentions the role schools have to play with regard to social transition:

“The importance of what happens in school cannot be under-estimated; this applies to all aspects of children’s health and wellbeing. Schools have been grappling with how they should respond when a pupil says that they want to socially transition in the school setting. For this reason, it is important that school guidance is able to utilise some of the principles and evidence from the Review.”

(page 158, Cass Review)

The Review outlines some principles and evidence as follows:

“Social transition… may not be thought of as an intervention or treatment, because it is not something that happens within health services. However, it is important to view it as an active intervention because it may have significant effects on the child or young person in terms of their psychological functioning. There are different views on the benefits versus the harms of early social transition. Whatever position one takes, it is important to acknowledge that it is not a neutral act, and better information is needed about outcomes.“

(page 62-63, Cass Review Interim Report)

“[I]t is possible that social transition in childhood may change the trajectory of gender identity development for children with early gender incongruence.”

(page 32 , Cass Review)

“There are different views on the benefits versus the harms of early social transition. Some consider that it may improve mental health for children experiencing gender-related distress, while others consider that it makes it more likely that a child’s gender dysphoria, which might have resolved at puberty, has an altered trajectory potentially, culminating in life-long medical intervention.”

(page 31, Cass Review)

“Given the weakness of the research in this area there remain many unknowns about the impact of social transition. In particular, it is unclear whether it alters the trajectory of gender development, and what short- and longer-term impact this may have on mental health.”

(page 163, Cass Review)

It also makes the following important point:

“[T]he Review heard concerns from many parents about their child being socially transitioned and affirmed in their expressed gender without parental involvement. This was predominantly where an adolescent had “come out” at school but expressed concern about how their parents might react. This set up an adversarial position between parent and child where some parents felt “forced” to affirm their child’s assumed identity or risk being painted as transphobic and/or unsupportive.“

(page 160, Cass Review)

The ‘good practice’ recommendations in the guidance substantiates these parental concerns: “A transgender young person may not have told their family about their gender identity. Inadvertent disclosure could cause needless stress for the young person or could put them at risk and breach legal requirements. Therefore, it is best to not share information with parents or carers without considering and respecting the young person’s views and rights.”

(page 35, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

This is a government that was prepared to allow 16 year olds to permanently change their sex in law. That was very much not a ‘neutral act’. The practice of teachers facilitating social transition at school is likely to remain in the third edition.

Chance of change in the third edition: VERY LOW

4. Concealment of Sex

The guidance supports concealing a child’s sex.

“[T]ransgender young people who join your school after transitioning may want to keep their gender history private, and this should be respected.”

(page 21, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

“[I]t is not necessary for all staff in a receiving school to know that the young person is transgender.“

(page 35, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

It is difficult to see how the duties required of schools under the Equality Act 2010 can be met if the sex of pupils is concealed. If the Scottish Government thinks that this is possible then it should clearly set out how, including appropriate consideration given to safeguarding responsibilities. However, given the equivocatory language used (of course ‘all staff’ will not need to know, no-one is suggesting briefing the cleaners), clarity from the Scottish Government is unlikely.

“It is often said that school records are considered a legal record. This reflects the processing of the information within the school record in line with a regulatory requirement. However, no legal steps are required for a change of name or recorded sex within a school record.”

(page 23, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

“It is often said” is a strange formulation for the guidance to use when talking about a regulatory requirement. Assuming this requirement relates to data collection for the purposes of equality monitoring under the 2010 Equality Act, then the guidance should instruct schools to follow the law; sex refers to biological sex.

More equivocation and prevarication is likely wherever possible but sections that relate to legal obligations are expected to be updated.

Chance of change in the third edition: FAIR

5. Freedom of Belief

The guidance frames declining to use preferred pronouns as bullying.

“Transphobic bullying can include: Deliberately using the wrong name and/or pronoun. This is different from people trying their best and making a mistake”

(page 17, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

“Staff should take care not to ‘out’ a young person by using a pronoun which differs from the one which the young person usually uses in public. Similarly, staff and young people should avoid misgendering a transgender young person. Using the correct pronouns is the right and respectful approach to including transgender young people.”

(page 25, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

After Forstater v CGD Europe EAT, the belief that sex cannot be changed is protected in law, and the UK Supreme Court has ruled that sex in the Equality Act means biological sex. In contrast, the concept of self-identification is a belief system not supported in law or objective reality. By instructing other pupils to adhere to the tenets of this belief system that they may not share, schools would risk infringing on children’s rights under article 14 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The situation is more complex for teachers. There has been no case law since the Supreme Court ruling, and cases preceding this have tended to find against teachers who have misgendered pupils. Teachers have professional responsibilities that pupils do not and the power dynamic is also an important consideration, both in the act of affirming/validating by using chosen pronouns, and in declining to do so.

The Scottish Government might clarify the guidance around misgendering by pupils, but any change is highly unlikely for teachers and other school staff.

Chance of change in the third edition: LOW

6. ‘Misconceptions’

The guidance makes several mentions of ‘misconceptions’ and ‘misinformation’ when discussing concerns that may be raised by parents and carers.

“If young people, or their parents/carers, express concerns about sharing toilets or changing rooms with a transgender young person, it may be because they are concerned that the transgender young person may behave inappropriately. In this instance, schools should seek to dispel any misconceptions: a transgender young person’s presence does not constitute inappropriate behaviour.”

(page 28-29, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

“Listen to the concerns of parents and carers without judging them; respond to concerns calmly; and correct any misconceptions.”

(page 39, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

“Address any misconceptions they may have”

(page 47, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

“concerns may be based on misconceptions or misinformation”

(page 46-47, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

When parents raised concerns about the first iteration of the guidance, LGBT Youth Scotland wrote to schools about this, asserting that they were “spreading misinformation”.

This has been a repeated accusation against people, mainly women, who are not misinformed at all, but who simply have an opposing point of view. This opposing point of view has won out in the highest court in the land, so it should really be time to either put the accusation of ‘misinformation’ to bed, or to spell out exactly what constitutes misinformation. At present, it is this guidance which is the prime culprit, not parents raising concerns.

Prevarication and equivocation are hallmarks of the Scottish Government on this issue. Why directly articulate what might constitute a reasonable (or unreasonable) concern when you can make vague references to ‘misconceptions’ and avoid having to defend your untenable position?

Chance of change in the third edition: LOW

7. Signposting

While the guidance states that “[t]eachers should always provide impartial information and guidance” (page 39, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools) that doesn’t seem to extend to this guidance document itself. The sources of support listed include LGBT Youth Scotland and Mermaids.

LGBT Youth Scotland takes a particular position on transgender issues; it is a political and contentious position and it cannot reasonably be described as impartial. In addition, the safeguarding standards of this organisation have been called into question, there have been two paedophiles linked to the charity, and both Edinburgh City Council and Children in Need have withdrawn funding from them.

Mermaids has very similar issues to LGBT Youth Scotland over its lack of impartiality, a link to paedophilia, and the Charity Commission finding that it had been mismanaged.

Given that LGBT Youth Scotland receives hundreds of thousands of pounds of funding from the Scottish Government, it is highly unlikely that they’re going to cut them loose on this.

Chance of change in the third edition: VERY LOW

8. Stereotypes and Gender Identity

The guidance states:

“[D]espite some recent progress, in society, boys are generally expected to be unemotional, strong, attracted to girls, sporty and to conform to ideals of masculine physical attractiveness. Girls are generally expected to be nurturing, emotional, helpful, attracted to boys, and to conform to ideals of feminine physical attractiveness. These are called gender ‘stereotypes’, ‘gender norms’ or ‘gender rules’…Transgender young people ‘break’ these gender rules because their gender identity does not match the sex assigned to them at birth, or they express their gender in a way that others do not consider ‘normal’.”

(page 49, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

Gender stereotypes can be thought of as an equation:

Girl = nurturing, emotional, conforms to ideals of feminine physical attractiveness etc,

Boy = unemotional, strong, conform to ideals of masculine physical attractiveness etc.

‘Breaking these rules’ would involve switching the equation so that: Girl = unemotional, strong, masculine and Boy = nurturing, emotional, feminine.

To suggest that transgender young people ‘break these rules’ would only make sense if girls identifying as boys were nurturing, emotional and conformed to ideals of feminine attractiveness and boys identifying as girls were unemotional, strong and conformed to ideas of masculine physical attractiveness.

In actual fact, the concept of gender identity and transgenderism is simply an inversion of the stereotype equation. Rather than Girl = nurturing, emotional, feminine it becomes nurturing, emotional, feminine = Girl.

This is neatly illustrated by a book the guidance recommends on page 64, I am Jazz by Jazz Jennings. Jazz’s favourite things are all stereotypically feminine; princesses, mermaids, high heels, and they are listed in the first couple of pages as evidence that Jazz has “a girl brain but a boy body”. Rather than being a gender non-conforming little boy, Jazz is made to conform: “whenever we went out I had to put on my boy clothes”. He is eventually taken to the doctor. After being diagnosed as ‘transgender’, Jazz is finally allowed to wear “girl clothes” and grow his hair long, not because little boys are allowed to do these things, but because he is really a ‘girl’. And as such, he is allowed to use the girls bathrooms and play on the girls sports team.

The guidance defines ‘gender identity’ as “a person’s deeply-felt internal and individual experience of gender. This may or may not correspond with the sex assigned to them at birth.” (page 49, Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools)

There is no definition of what gender is, or how a child might experience it other than ‘individually’ and ‘internally’. In contrast, current RSHP learning resources are incredibly unambiguous about sex. There are clear definitions and diagrams with labels, so that children are able to look at their own bodies and understand whether they are a boy or a girl. When it comes to gender identity however, children are left to work it out for themselves. Gender identity seemingly has no properties, qualities or attributes. There is no distinction ever made between how ‘girl’ gender identity differs from ‘boy’ gender identity. All children are provided with to guide them are books like I am Jazz which tell them that it is their adherence or not to stereotypes that determines whether they are really a girl or a boy.

There is a poster on page 46 with a picture of two boxes labelled ‘girl’ and ‘boy’ with a lock illustration and the legend ‘gender is not this’.

Again, there is no definition provided for the word ‘gender’.

- Read as a synonym for sex, then this poster appears to be suggesting that sex is something other than male and female. This is obviously untrue.

- A reading of gender as a social construct might seem to relate to stereotypes, and this would make sense if the boxes contained things relating to masculinity and femininity, although ‘gender is not this’ would no longer make sense. However, in labelling the box ‘girl’, it appears that the only way to get out of the confines of the box is to reject ‘girl’ itself.

- If gender is taken to mean gender identity, it would be wonderful to know what exactly is making up the walls of the box. If gender identity is an ‘individual experience of gender’, how exactly is that confining? What is boy gender identity? How is it different from girl gender identity, so much so that they would be locked in separate boxes?

These kinds of unpickings have all been put to the Scottish Government many times over with absolutely no indication of any level of understanding forthcoming or of any attempt to engage with these questions.

Chance of change in the third edition: ZERO

The current Scottish Government guidance on supporting transgender pupils is untenable, being both unlawful and in direct conflict with the evidence from the Cass Review. While court rulings will likely force its withdrawal and revision on legally clear-cut issues like single-sex spaces, the government’s deep-seated ideological position is likely to prevent other essential changes. It is hard not to question just how many more editions will need to be published and withdrawn before teachers and parents finally have guidance they can trust to be lawful, evidence-based, and fit for purpose, and how much damage will be done to children in the meantime.